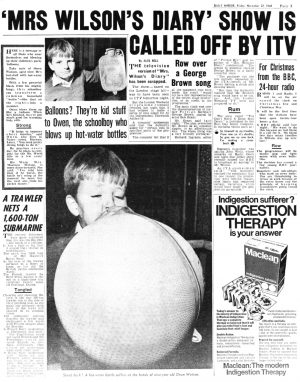

The significance of George (with or without bottle) and how you vote

The famous stage satire Mrs Wilson’s Diary is about to make its way on to London Weekend… no thanks to the ITA, writes Milton Shulman

Someone at the ITA is finally showing some common sense, and a little courage, I would like to think it is Lord Aylestone.

Mrs. Wilson’s Diary, the political satire about life at 10 Downing Street, has been declared clean and acceptable for viewing. It is scheduled for January 4.

The controversy that kept it off the air last month, when it was due to go on, was always pretty much a storm in a hip flask

Should the public be allowed to see an actor portraying George Brown staggering around the stage waving a bottle and singing, “Give me the rum back, I’m making a come-back”?

The ITA felt that such a scene was “contrary to good taste or offensive to public feeling.” The fact that a character named Brown had been doing exactly the same thing for many months at the Criterion in London’s West End did not, in the authority’s view, make a tolerable.

Nor did they feel that their decision to eliminate these lines should be reversed by the mere fact that almost every paper in the country, in reporting the incident, had already printed the offending lyric that was presumably against ‘good taste.’

On this major issue, Lord Aylestone or somebody dug in his toes, and London Weekend TV decided to cancel the transmission.

It is an interesting sidelight of this silly squabble that one of the major causes of the elimination of the Lord Chamberlain’s power to censor plays was the argument that TV, as demonstrated in the satire shows, had more freedom to comment on politics than the theatre.

Freedom

Now we have the reverse situation of a play that had already been seen by many thousands in London — and had been passed by the Lord Chamberlain – but could not be shown to a wider public on TV because someone at the ITA had greater sensibilities about political satire than even the Lord Chamberlain.

Second thoughts have however, won the day. Mr. Brown and the bottle have been eliminated. In its place the telly public will see instead “Mr. Brown” asking “Mr. Wilson”: “What happens if you’re run over by a bus?” which is followed up by “Mr Brown” singing the lines. If destiny calls me, can I refuse? Though bright lights appal me I’m still bloody big news.” Sung, I am assured, sans bottle.

By such a narrow margin is good taste maintained, the public saved from offensive feelings and the dignity of politicians preserved.

The larger question raised by this issue is the nature and extent of the freedom to be given to broadcasting authorities in their handling of politics and politicians.

Compared to the lethal barbs that were shot at Sir Alec Douglas Home [Prime Minister 1963-4 – Ed], Henry Brooke [Home Secretary 1962-4] and Anthony Eden [Prime Minister 1955-7] in the hey-day of the BBC’s satire phase, Mrs. Wilson’s Diary is comparatively amiable stuff.

Such, however, is the fear of politicians for the television medium that what they will countenance from cartoonists, newspapers, music-hall and theatre, they will do their damnedest to throttle on television

Yet a recently published book, Television in Politics, by Jay G. Blunder and Denis McQuail, would seem to indicate that TV is not merely the terrifying, formative monster — anarchically reshaping political attitudes – that politicians think it is.

Based upon a sample of 748 electors in the West Leeds and Pudsey constituencies during the election campaign of 1964, the authors conclude that TV only marginally influenced voters during this three-week period of intensive electioneering.

Smug

The book also revealed that the Liberal Party, given more TV time, did better because of this extra screen exposure; that party political broadcasts were useful in imparting knowledge about the issues; and that there was not sufficient hard evidence to determine just how much leaders like Home or Wilson helped or hindered their parties by their TV appearance.

While accepting the validity of these largely obvious findings, I feel that in its writing down of the significance of TV on politics the book may lead to some glib and smug conclusions.

I suspect that the reason this detailed survey has produced such undramatic results is because its area of investigation has been too narrow and too limited.

It was surely obvious that a short, three week campaign could have only marginal impact on attitudes already hardened before the campaign began.

The converted would look only for confirmation for their opinions; the unconverted — the much smaller segment of the electorate – would use TV, along with other sources, for making up their minds.

Conditioned

But what caused political altitudes to harden in the first place? What part did TV have between elections, in determining the polarisation of political opinions?

Only in two areas does this book touch upon this much more important issue. The electorate overwhelmingly rates TV as the most up-to-date, impartial and trustworthy medium in aiding it to weigh up political problems.

The survey also showed that voters have little faith in the integrity and honesty of politicians. No less than two fifth of the voters found politicians “usually” unreliable and misleading. Only 15 per cent. thought they were fairly reliable.

Since TV is to be trusted and politicians are not to be trusted, how much of the attitude is conditioned by the former?

It is the long-term impact of that is surely more important than the short-term. If a child is conditioned all his formative years to watch his leaders cavorting in a trivial and superficial environment, is it any wonder that he views the entire political spectrum with contempt?

Is not the five-year period between elections – as we watch it on TV – more significant in determining how people will vote, and their attitude to political leaders, than the short burst of three weeks’ frantic activity during an election campaign?